At a glance

This page covers PFAS epidemiology, exposure sources and routes, and drinking water standards, regulations, and health.

Epidemiology

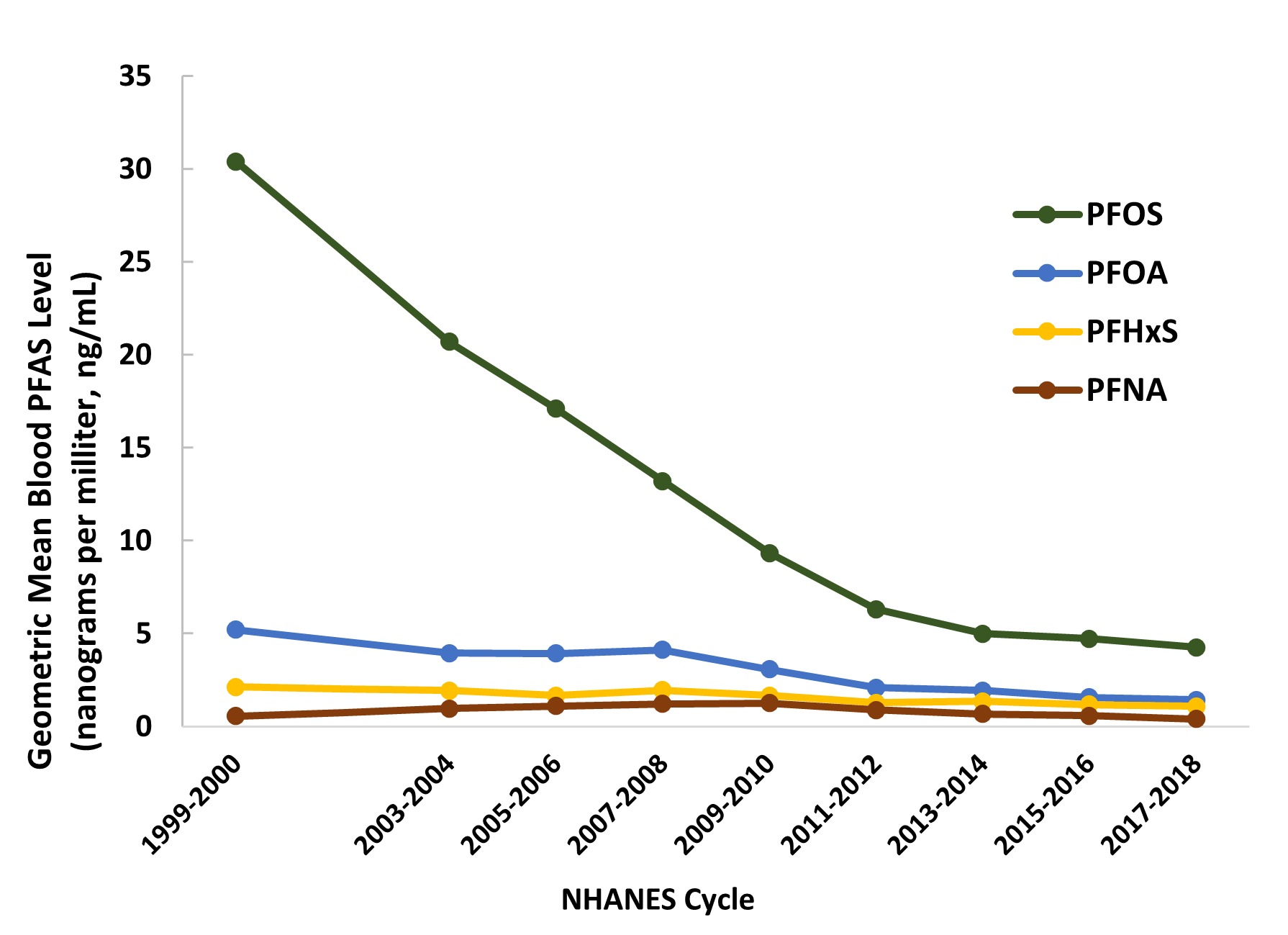

Nearly all people in the United States have measurable amounts of PFAS in their blood. Researchers often use people’s blood PFAS levels as a proxy for exposure. Since 1999, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) has been measuring certain PFAS (e.g., PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, and PFNA) in blood samples from people living in the United States. The data show declining levels of three prevalent PFAS (PFOA, PFOS, and PFHxS), in part because the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) enlisted major manufacturers to phase out production and reduce facility emissions of PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, and PFNA. Population blood levels of substitute PFAS (e.g., GenX) are not well studied. Blood levels of these shorter-chain PFAS do not necessarily reflect total cumulative exposure because they tend to have relatively short half-lives.

In 2017–2018, NHANES reported geometric mean blood levels of

- PFOS: 4.25 ng/mL*, with 95% of the general population ≤14.6 ng/mL,

- PFOA: 1.42 ng/mL, with 95% of the general population ≤3.77 ng/mL,

- PFHxS: 1.08 ng/mL, with 95% of the general population ≤3.70 ng/mL, and

- PFNA: 0.411 ng/mL, with 95% of the general population ≤1.40 ng/mL.

*Nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL) is equivalent to micrograms per liter (µg/L) and to parts per billion (ppb).

Some communities can have higher geometric mean levels of blood PFAS than NHANES.

Exposure sources and routes

Communities with documented PFAS contamination in drinking water supplies or food are often near facilities that have manufactured, used, or handled PFAS; these include some factories, airports, military bases, wastewater treatment plants, farms where sewage sludge was used for fertilizer, landfills, or incinerators. Other PFAS exposure sources include PFAS-containing consumer products and workplaces that manufacture, use, or handle PFAS.

Routes of exposure to PFAS include ingestion, placental transfer, and inhalation. Dermal absorption of PFAS is limited and does not appear to be a significant route of exposure for the general population. For more information on occupational exposures, please visit the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) PFAS webpage.

Ingestion

Ingestion of food and water is a main route of PFAS exposure. In communities affected by PFAS-contaminated drinking water, water can be the main source of exposure. For other communities, the relative contribution of exposure sources can vary.

Ingestion of PFAS can occur through

- drinking water from PFAS-contaminated municipal sources or private wells,

- eating food (e.g., meat, dairy, and vegetables) produced near places where PFAS were used or made,

- eating fish caught from water contaminated by PFAS (PFOS, in particular),

- eating food from some types of grease-resistant paper or packaging (e.g., popcorn bags, fast food containers, pizza boxes, and candy wrappers), and

- swallowing contaminated soil.

Ingestion of residue and dust from PFAS-containing consumer products is another way people are exposed to PFAS. Research has suggested that exposure to PFOA and PFOS from today's consumer products is generally lower than exposures from PFAS-contaminated drinking water. Some products that might contain PFAS include

- stain-resistant carpets, upholstery, and other fabrics,

- water-resistant clothing,

- cleaning products,

- personal care products and cosmetics (e.g., shampoo, dental floss, nail polish, and eye makeup), and

- paints, varnishes, and sealants.

Children can have higher PFAS exposures through ingestion than adults. Children eat and drink more relative to their body weight and can ingest dust or dirt containing PFAS through mouthing objects and hand-to-mouth behaviors. Children can also be exposed by

- drinking formula mixed with PFAS-contaminated water, and

- drinking breastmilk from persons exposed to PFAS.

Placental transfer

Some PFAS cross the placenta and enter umbilical cord blood. The permeability of the placental barrier varies for different PFAS.

Inhalation

Most PFAS are not volatile, so inhalation is not a typical exposure route for the general population. People living near facilities that incinerate PFAS and PFAS-containing materials can be exposed to PFAS through inhalation.

In the workplace, handling of PFAS and PFAS-containing materials and breathing associated dust, aerosols, or fumes can also result in exposure to PFAS through inhalation. Inhalation is not a typical route of exposure for the general population but can occur with use of some PFAS-containing consumer products.

Drinking water standards, regulations, and health advisories

Federal and state PFAS drinking water standards as well as health advisories for PFAS may differ and can be expected to change over time. In general, PFAS drinking water standards, regulations, and health advisories are not intended for use in assessing an individual patient’s health risks, but following these can help reduce drinking water exposures to PFAS.

- [ATSDR] Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2021. Toxicological profile for perfluoroalkyls. U.S. Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA [accessed 2023 May 4]. Available from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp200.pdf

- [CDC] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA [accessed 2023 May 4]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/index.html

- [NASEM] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2022. Guidance on PFAS Exposure, Testing, and Clinical Follow-Up. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Available from: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26156/guidance-on-pfas-exposure-testing-and-clinical-follow-up